When families think about what sends an aging parent to a nursing home, they tend to think of a single, dramatic event: a fall, a stroke, a hip fracture, a dementia diagnosis. But a large-scale analysis of more than 16,000 older Americans tells a different story. The path to institutional care is rarely a sudden turn. More often, it is a slow fade. A gradual loss of the ability to manage daily life that accumulates quietly, over years, before anyone names it.

Using data from the Health and Retirement Study, one of the most comprehensive longitudinal surveys of aging in the United States, we trained a machine-learning model to identify which characteristics best predict who will enter a nursing home over the following decade. The model considered 27 factors spanning demographics, chronic diseases, physical function, cognition, and mental health.

The bottom line: nursing home entry is not primarily a story about diagnoses. It is a story about the slow, cumulative loss of the ability to manage everyday life. The model sees it coming years in advance. The question is whether we will learn to see it too, and act while there is still time to change the trajectory.

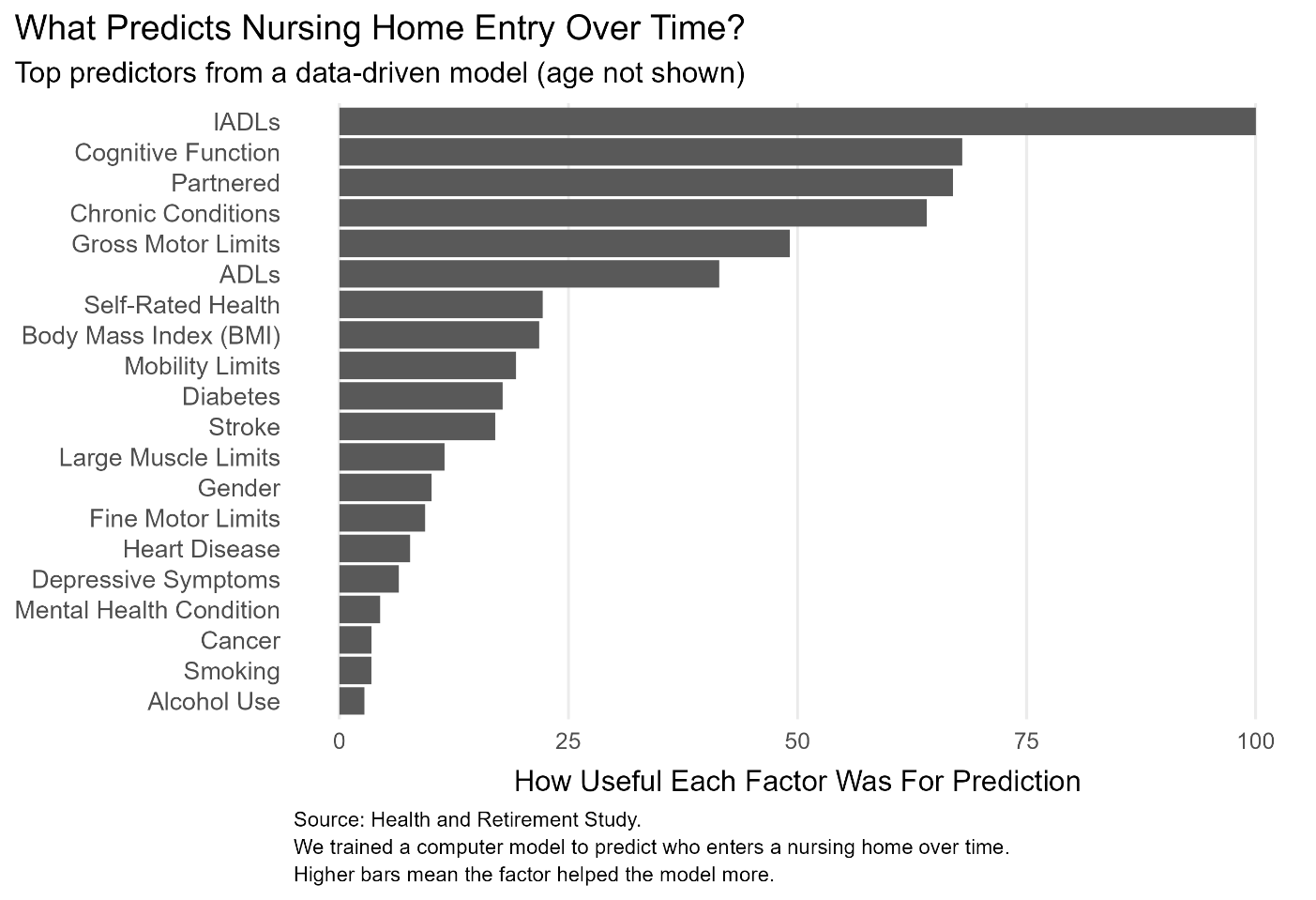

Figure 1: The strongest signals are not diseases

The chart below ranks every factor by how much it improved the model’s predictions. The results are striking. The single most powerful predictor was not a diagnosis at all; it was difficulty with instrumental activities of daily living, or IADLs: tasks like managing finances, preparing meals, using a telephone, and taking medications. Cognitive function ranked second. Whether someone had a spouse or partner came third.

Chronic conditions, the total number of diagnosed diseases, mattered in aggregate, but individual diagnoses like heart disease, cancer, and lung disease ranked near the bottom. Diabetes and stroke carried moderate weight, likely because they accelerate functional decline.

This is an important distinction. The model is not saying that diseases don’t matter. It is saying that what diseases do to your daily functioning matters more than the disease label itself. Two people can have the same diagnosis of diabetes. The one who can still cook, drive, and manage medications is in a fundamentally different position than the one who cannot.

Figure 1. The factors that best predict nursing home entry over time. IADLs (instrumental activities of daily living), cognitive function, and partnership status dominated. Age is excluded from the chart because it is used to define the time scale. Source: Health and Retirement Study.

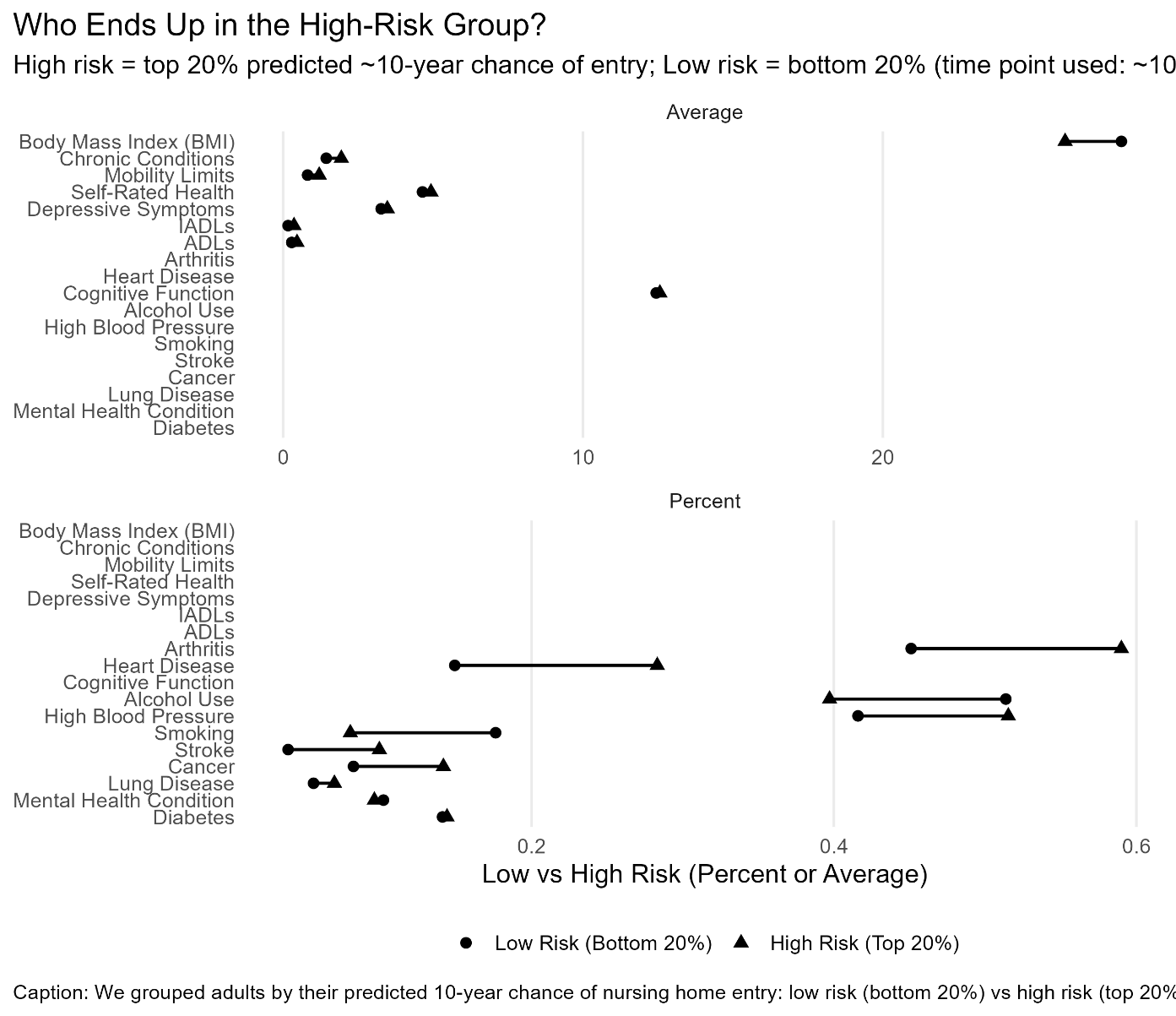

Figure 2: Who’s at risk?

To understand who the model flags as vulnerable, we compared the 20 percent of adults with the highest predicted risk to the 20 percent with the lowest. The differences are not subtle. The high-risk group had dramatically more difficulty with daily tasks, both basic activities like bathing and dressing (ADLs) and more complex ones like shopping and managing money (IADLs). They had more mobility limitations, worse self-rated health, more depressive symptoms, and lower cognitive scores. They were also less likely to have a partner, which matters because spouses are often the first and last line of informal caregiving.

What is perhaps most notable is how ordinary these differences look in isolation. A few more points of difficulty on a mobility scale. A slightly lower cognitive score. A bit more trouble with household management. None of these, alone, would trigger an alarm in a doctor’s office. But together, they paint a portrait of someone who is already losing ground.

Figure 2. How high-risk and low-risk adults differ at baseline. Each row shows a characteristic; the gap between dots shows the difference between the bottom 20% (low risk) and top 20% (high risk) of predicted 10-year nursing home entry probability. Source: Health and Retirement Study.

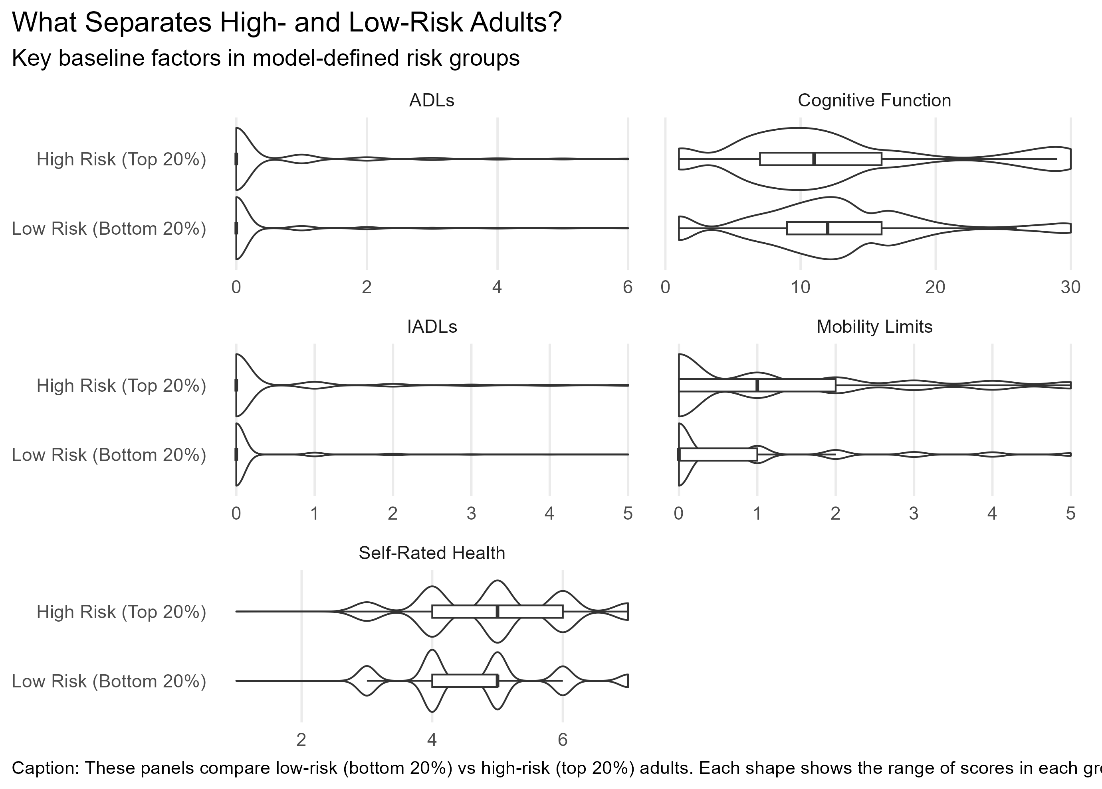

Figure 3: The gap in everyday function

The clearest way to see the divide is to look at how the two groups are distributed across the key measures. The plots below show the full range of scores for five critical factors. In every case, the high-risk group is shifted toward greater difficulty or lower capacity.

In looking at cognitive function, the low-risk group clusters tightly around higher scores, while the high-risk group spreads across a much wider, lower range. For ADLs and IADLs, the low-risk group is overwhelmingly concentrated at zero (no difficulty) while the high-risk group fans out across multiple levels of impairment. Mobility limitations and self-rated health tell the same story.

This is not a binary switch. It is a gradient. People do not wake up one day unable to care for themselves. The data show that long before nursing home entry, there are measurable signs, distributed across multiple domains of function, that distinguish who is headed toward institutional care and who is not.

Figure 3. Distributions of five key baseline factors for low-risk (bottom 20%) versus high-risk (top 20%) adults. High-risk adults cluster where cognitive function is lower and functional difficulty is higher. Source: Health and Retirement Study.

What does it all mean?

The implications are both concerning and, in some ways, hopeful. Concerning, because the findings suggest that by the time many families start thinking seriously about nursing home risk (usually after a hospital stay or a frightening fall) the underlying trajectory has been building for years. The signs were there in the small struggles: needing help with bills, giving up driving, having trouble with stairs.

But hopeful, because functional decline is, to a greater degree than many diagnoses, something that can be slowed. Physical therapy, cognitive engagement, medication management, home modifications, and caregiver support all target the very domains this model identifies as critical. If the strongest predictors of nursing home entry are not diseases themselves but what diseases do to daily functioning, then interventions that preserve function even modestly may meaningfully delay or prevent institutionalization.

The data also underscore the protective power of partnership. Having a spouse or partner was the third strongest predictor, stronger than any individual disease. This is not merely a reflection of shared finances. Partners notice decline early. They provide daily assistance that keeps the system working. When that support disappears through death, divorce, or their own declining health the risk of institutional care rises sharply.

About This Analysis

Data come from the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative longitudinal survey of Americans over age 50, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging. We used Wave 5 baseline data and followed participants for nursing home entry. The model is a random survival forest with 1,000 trees, fit to approximately 16,650 respondents with complete or imputable data on 27 predictors. Variable importance was assessed via permutation. Risk groups reflect the top and bottom 20 percent of predicted 10-year nursing home entry probability. Age was used to define the survival time scale and is excluded from the variable importance chart.