Moving to a retirement community is a major life change – one that can bring exciting new opportunities, but also significant expenses. Whether you’re a retiree planning your next chapter or an adult child helping your parent make the transition, it’s crucial to understand all the costs involved. Below our team breaks down the financial and logistical aspects of moving into a retirement community in the United States. We’ll compare in-state vs. out-of-state moves, explain types of retirement communities (independent living, assisted living, and CCRCs), uncover obvious and hidden costs (from real estate fees to healthcare and taxes), and offer tips for planning a smooth transition. Let’s dive in, so you can make an informed decision and avoid surprises along the way.

In-State vs. Out-of-State Moves: Financial and Logistical Differences

Long-distance interstate relocations tend to be far more costly and complex than local in-state moves.

- Moving Costs: Distance is a major cost factor. In-state moves (especially if under ~100 miles) are often considered “local” moves. The average local move costs about $1,700 (with typical ranges from ~$880 up to $2,500). In contrast, an interstate move can easily cost several times more – often $2,700 to $10,000+ for a long-distance relocation.

- Logistical Complexity: An out-of-state move can involve more planning. You may need to coordinate interstate movers (who are licensed for long-distance transport), deal with different state regulations (for driver’s licenses, vehicle registration, insurance, etc.), and possibly make scouting trips beforehand to tour communities. In-state moves are generally simpler – you might be able to make multiple smaller trips in your car, and you’re staying within familiar state systems (same state tax rules, healthcare network, etc.).

- Settling In and Services: Moving farther away often means starting fresh with service providers. If you move out-of-state, you may need to find new doctors, transfer prescriptions to a new pharmacy, and get used to a different healthcare network. You’ll also be learning a new area’s amenities and possibly a different climate or culture. Staying in-state, especially within the same region, could mean you remain closer to your current friends, physicians, and routines (making the transition a bit easier).

- Tax and Cost of Living Differences: Changing states can affect your cost of living. Some retirees purposely relocate to states with more favorable tax climates or lower living costs. For instance, moving from a high-tax state like New York to a state like Florida or Texas (which have no state income tax) can save money on taxes – pensions, 401(k) withdrawals, and Social Security benefits would not be subject to state income tax in those no-tax states. On the other hand, states differ in sales taxes, property taxes, and home prices, so evaluate the overall impact. (We’ll discuss tax implications more below.)

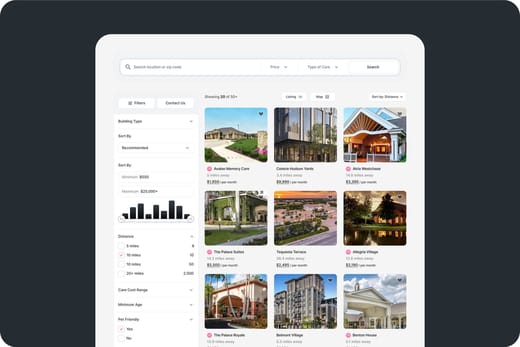

Understanding Types of Retirement Communities

Not all retirement communities are the same. It’s important to choose a community type that fits your needs, lifestyle, and budget. Here are the main types:

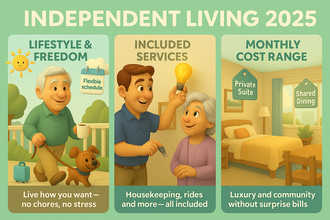

Independent Living Communities (Active Adult Communities)

Independent living communities are designed for older adults who are self-sufficient and want to live among peers in a convenient, maintenance-free setting. These can be age-restricted communities (like “55+” communities, retirement villages, or senior apartment complexes).

- Features: Residents typically live in private apartments or cottages. Communities often provide amenities like dining venues, housekeeping, transportation, fitness centers, and social activities – but they do not provide daily personal care or medical assistance. The focus is on convenience and social life for active seniors who can manage their own basic needs

- Costs: Independent living is generally the least expensive of the senior living options because it excludes healthcare services. Costs are akin to renting an apartment with some added services. Monthly fees usually cover rent and some utilities, with optional add-ons for meal plans or amenities. Nationally, the median monthly cost of independent living is about $3,065, though it varies by location and community level (some simpler communities might be $2,000/month, while luxury ones in high-cost cities can be $5,000+). These communities typically do not require large upfront entrance fees – you might pay a security deposit or community fee, but you’re not “buying in” as you would with other models.

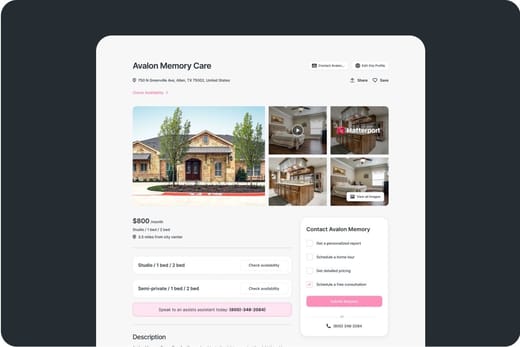

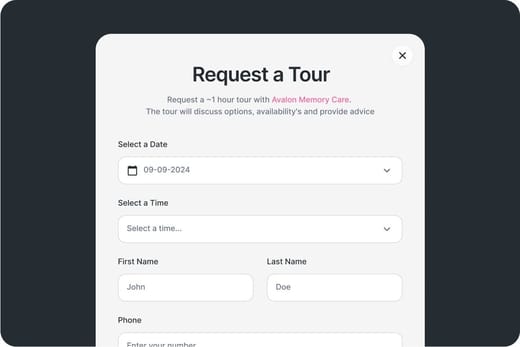

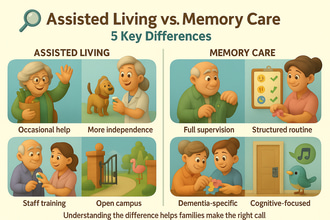

Assisted Living Facilities

Assisted living is geared toward seniors who need help with daily activities (like bathing, dressing, medication management, or mobility) but who do not require 24/7 medical nursing care. In assisted living, residents still have private apartments or rooms, but with caregivers on staff to support their needs.

- Features: The monthly fee at an assisted living facility usually includes room and board, daily meals, housekeeping, transportation, and personal care assistance. These communities often have nurses on-site or on-call, organized social activities, and amenities similar to independent living – but with an added layer of care. It’s an ideal option if living independently is becoming challenging, yet the person doesn’t need a nursing home’s level of medical care.

- Costs: Assisted living is more expensive than independent living due to the added caregiving services. The median cost of assisted living in the U.S. is roughly $6,000 per month as of 2025. In some regions it may be closer to $4,000, whereas in expensive urban areas or for higher levels of care it can run $8,000 or more. This monthly fee covers the basics of care; however, note that many facilities have tiered pricing levels – if a resident’s needs increase (for example, they need memory care or extra one-on-one assistance), the monthly fee might increase accordingly. Unlike nursing homes, assisted living is often paid out-of-pocket (Medicaid coverage is limited and Medicare doesn’t cover it), so planning for these costs is key.

Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs or Life Plan Communities)

Continuing Care Retirement Communities offer a full continuum of care – from independent living to assisted living to skilled nursing – all on one campus. They allow residents to “age in place,” meaning you can move in while independent and then transition to higher care levels within the same community as your needs change over time. CCRCs are appealing for those who want a long-term plan and peace of mind about future care, but they come with a unique fee structure.

- Features: A CCRC typically has an on-site independent living neighborhood (apartments or cottages), an assisted living facility, and a nursing home. Residents might start in their own apartment, but if they eventually need nursing care, it’s provided within the community. Amenities in CCRCs are often extensive – multiple dining venues, pools or fitness centers, classes, social events, transportation, and more – essentially a small town of seniors with support services built in.

- Costs: Most CCRCs require a one-time entrance fee** (also called a buy-in fee) plus ongoing monthly fees. The entrance fee can be significant: often tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars upfront. The average entrance fee in the US is seen to be between 350k-400k and they can range from around $100,000 on the low end up to $1 million or more for upscale communities in pricey areas.

Costs of Moving to a Retirement Community: Obvious and Hidden Expenses

Relocating to a retirement community involves more than just the monthly rent or care fee. It’s a combination of one-time costs (like selling your home and physically moving) and ongoing costs (monthly fees, utilities, etc.), plus some intangible “costs” like emotional stress. We’ll cover each of these so you can budget properly.

Real Estate Transactions (Selling and Buying)

If the senior owns a home, one of the biggest financial steps is often selling the current house. The proceeds from the home sale might be used to fund the move or pay an entrance fee, but don’t forget the costs of selling:

- Realtor Commissions: Typically, 5%–6% of the home’s sale price goes to real estate agent commissions. For example, at the median U.S. home price (~$368,000), sellers pay about $20,000 in realtor fees on average.

- Home Repairs and Staging: Many people invest in sprucing up their house before selling – painting, minor repairs, landscaping – to get the best price. These prep costs can be a few thousand dollars (or more if major updates are needed) and should be budgeted as part of the move.

- Closing Costs and Taxes: Sellers may need to cover some closing costs (like transfer taxes, attorney fees, etc.), depending on local custom. Also, if the home has appreciated significantly, consider potential capital gains taxes. (Federal tax law usually exempts $250k of gain for single homeowners or $500k for couples on a primary residence sale, but very large gains above that could incur taxes. State tax laws vary on home sale gains.)

- Buying into the Community: In most retirement communities, you don’t actually purchase real estate (you pay rent or an entrance fee for the right to live there, rather than buying a condo). However, some communities – especially 55+ housing developments – might involve purchasing a home or condo unit. In those cases, you’ll have purchase costs similar to any real estate transaction (down payment, closing costs, possibly mortgage if not paying cash). For a CCRC or rental community, there could be a smaller “community fee” due at signing (for example, some assisted living places have a one-time community fee of a few thousand dollars). Be sure to ask what upfront fees are required beyond any entrance fee or deposit.

Moving and Transportation Costs

Actually moving your belongings is another significant expense. This will depend on how far you’re moving and how much stuff you have:

- Local Moves: If you’re moving within the same town or region, you might do it yourself with a rented truck or hire local movers by the hour. Hiring professional movers for a short-distance (intrastate) move costs roughly $900 to $2,500 in many cases. The average local move (~100 miles or less) runs about $1,700. This typically includes loading, transport, and unloading. You might reduce costs by handling the packing yourself and just hiring labor for the heavy lifting and truck.

- Long-Distance Moves: For interstate moves, costs increase with distance, weight of your goods, and any extra services. Cross-country moving services can easily range from $3,000 up to $10,000 or more. This may include packing services, insurance, transport, and sometimes short-term storage (if your move-in date at the community is delayed). Always get multiple quotes from moving companies and inquire about senior discounts – many movers offer discounts for seniors or military, etc.

- Temporary Storage: In some cases, you might not take all your belongings at once. You may choose to put items in storage (for instance, if you’re undecided about keeping certain furniture, or if your new place is still getting prepared). Budget for monthly storage unit fees and the cost for movers to move items into storage. Also, moving companies may charge for storage-in-transit if they hold your goods for a few days or weeks before delivery.

Remember: Get a detailed quote from movers and ask about any potential extra charges (for example, some charge extra for lots of heavy furniture, flights of stairs, long carry distances from the truck, or narrow elevators). Make sure the quote includes insurance for your belongings. If you’re doing a DIY move, don’t forget costs like truck rental, gas, packing supplies, and maybe hiring local help for loading/unloading.

Emotional and Transitional Costs

Lastly, not all costs are in dollars. There are emotional and social “costs” in leaving one home for another, even if it’s a positive move. Acknowledge these factors as part of the transition:

- Leaving Home and Community: For many seniors, moving out of a long-time family home is emotionally challenging. There’s a sense of loss or nostalgia in leaving a place filled with memories. Even if the physical and financial upkeep of the house was burdensome, it can be hard to let go. There may also be sadness in leaving neighbors and a familiar community. These emotions are normal, and it helps to talk about them. Adult children should be prepared for parents to have moments of doubt or grief over the move, even if they know it’s the right choice.

- Stress of Downsizing: Sorting through decades of belongings can be overwhelming. Deciding what to keep, what to give away, can stir up emotions. Family members might find it taxing as well – conflicts can arise over what to do with certain items or how quickly to move. It’s important to approach downsizing with patience and, if possible, a sense of celebration for the next phase rather than pure sadness for what’s being left behind.

- Adjustment Period: After the move, there’s usually an adjustment period. Adapting to new routines, new faces, and possibly a smaller living space takes time. It’s not uncommon for a senior (or anyone, really) to feel anxious, lonely, or disoriented in the first weeks after moving. They might express second thoughts or idealize their old home (“Did I make a mistake moving here?”). Families should try to visit or call frequently during this time and encourage the new resident to participate in activities to meet people. Retirement communities have staff and resident ambassadors who often help newcomers settle in – don’t be shy about tapping those resources.

- Impact on Family: Adult children and other family also feel the transition. If the senior moves out-of-state, the family might feel guilt or worry about not being close by. Or if the parent is moving in-state but from the family home, adult kids may feel sentimental about “losing” their childhood home. And of course, the process of helping a parent move can be physically and emotionally exhausting for the family. It’s a challenging transition for the whole family unit, so everyone should practice patience and understand that tempers or tears may flare during the process.

Despite these emotional costs, remember the potential emotional benefits: once settled, many seniors thrive in retirement communities. They often find new friends, enjoy activities, and feel safer knowing help is nearby. Adult children often feel relief that their parent is in a supportive environment. Keeping these positives in mind can help offset the bittersweet feelings of the move.

Relocating to a retirement community is a major financial and emotional milestone, and understanding the full range of associated costs—from moving logistics and healthcare needs to hidden lifestyle fees and state tax differences—can make all the difference in planning a smooth transition. Whether staying local or crossing state lines, the key is early preparation, honest budgeting, and leveraging professional and community resources. By accounting for both the obvious and less visible expenses, retirees and their families can make confident, informed decisions that support a safe, comfortable, and fulfilling next chapter.